Let's define Change around the creation of Value | Creating and Measuring Value

There is tension between Value as accounted for on financial statements versus by customers, operations and product development. Inspired by this tension, I consider my own experience leading change, and try to lay foundations for a Value-Driven Change Manifesto.

Photo by Alex Azabache on Unsplash

Despite what everyone likes to think, the default assumption in most companies is that customers are here to stay. We easily rationalize away the reason customers leave and blame ineffective sales for not getting more customers to join.

It is easy for everyone to believe that the way things are is the way they are supposed to be and are likely to remain. If I had a euro for every time I heard a business leader say "you don't understand, Vincent, this is how our customers like it" or "look, we've been doing this for years, we know what our customers want", well... I'd have a few hundred euros more.

Yet, in every company, if we pay attention and refrain from looking for excuses to feel good about ourselves, we will discover a myriad ways in which our company gets in the way of our customers accomplishing their goals. Yes, how our company, by design, prevents users from getting things done.

Think to yourself, how often have you consciously or subconsciously operated on the basis that your customers need the value provided by your product or service so much, that this dispenses you from making it easier for them to get to that value? That this value gives you a right to their time and money that you will use to your advantage?

Some of this levearge is understandable: as a creator of value, you need to capture some of it in ways that your CFO understands, and you need to make sure this number is as high as possible. For instance, you launch additional marketing campaigns, you upsell, you increase prices and introduce paid features and so on, to exercise that right to the value.

But I contend that the most important way in which we, human groups in companies, abuse our right to a slice of the value created, is to consider that the value that we provide gives us the right to keep doing things the same way we've always been doing them.

After all, that's what customers are paying for, isn't it?

Squeezing change out of the business process

As a result of this bias, whenever a change opportunity eventually makes it to the strategy meeting, the perception by operational, sales, marketing folks is that, sure, I can see how this change aims at increasing profits for the company, but:

- I'm once again going to be asked to do more for less,

- I will be asked to sacrifice the integrity of my professionalism to increase shareholder returns,

- the quality of the product or service is going to suffer.

In a nutshell: the base cultural assumption in a company when some change program is being rolled out is that it is designed to squeeze the organization more than it already is.

Of course, we all know about how most of us are change-averse. We don't like things to change, unless the change is something we came up with to make our lives easier. But this "change aversion" trope, while obviously not false, is a concept that change leaders fall back to easily to avoid accountability for the bad quality of our change goals.

"Hey, my change program is going to save millions of dollars, and I'm a great leader, but whatchagonnado, people are so change-averse...."

Now, the question is: to what extent are executive change leaders responsible for this? Well, I believe that, for all intents and purposes, we're responsible for all of it. As leaders defining change goals in our organization, we're the reason people feel that way about the change that we're selling.

The truth is, there are very legitimate reasons why the organisation fears change. It is common for change programs to be designed exactly from a squeeze perspective, we've all been there. I know I've conducted change of that type in the past. In fact, I made a chunk of my career on that kind of change, and it's not what makes me feel most accomplished in hindsight.

Over decades of leading change in different contexts, I now know that change leaders are just as averse to change as any other average employee. Our anchor is just of a different nature than the anchor of professional teams delivering and selling the products: executive change leaders are averse to thinking differently about value creation. We take the business as it is, and we find ways to reduce our costs. If we're really creative, we also look for ways to sell more products.

In other words, a typical change program is designed by counting beans and trying to push beans from the middle of the income statement to the bottom line. And, sure, ultimately, this where value is accounted for. But the income statement is only an after-the-fact artefact resulting from a very complex process of value creation.

Modeling the Value beyond the observables

"Observables" are what physicists call the measurable properties of objects that only exist by virtue of the act of measurement, irrespective of what was going on beforehand or what would have gone on otherwise. When a physicist observes a trace in a detector at the LHC, they are looking at the income statement resulting from the massively complex set of interactions that occurred at the point of collision. Everybody knows that observables are not what is actually going on. But then how do they have a clue about what actually happened that they can't see?

They rely on a detailed model of particles, a consistent theory that describes particle properties and interactions, and by counting the beans on the detector, they can tentatively reconstruct a picture of how the collision energy was actually used and dissipated. What matters to them is not the traces on the detector, not the income statement, it's the amazing and varied ways in which what actually happened left these simple traces on the detector.

Getting back to business, believing that the financial reporting is an accurate representation of what goes on in the enterprise is the key, central error. In order to change the balance of beans on the income statement and have more remaining at the end, we have to understand where and how value is created in the enterprise and that the beans that remain at the bottom are only a partial property of it that we are capturing. The true value produced by the enterprise is far greater than that, and it is not represented by these beans.

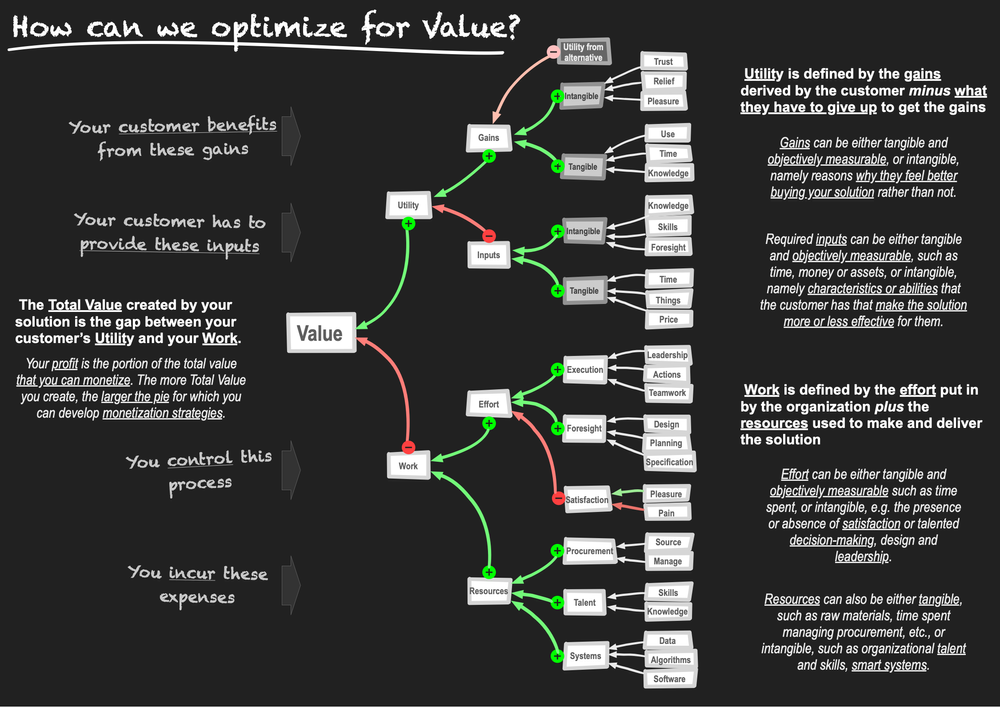

Value is the gap between the desire for a utility and the effort and resources required to fulfil that desire. Between a willingness to pay and an ability to sell. Now the key thing is this: not all value is immediately tangible. Some of the value is intangible and provides benefits that are not immediately or easily measurable as P&L for the buyer or the seller. Yet, this intangible value influences both the willigness to pay and ability to sell.

I say this: our business transformation programs are too narrrow-minded and focus on counting observable beans rather than figuring out:

- how and where is value created in the array of interactions that happen between all the business process stakeholders?

- how much of the created value are we capturing?

- who is capturing the rest of it?

- can we increase total value creation?

- can we retain more of it?

- can we also increase the amount of value captured by our customers?

- can we also increase the amount of value captured by our suppliers?

Answering these questions, one at a time, based on a solid understanding of where value is created, multiplies the opportunities of improving return on capital.

Focusing only on simple questions like "how can I reduce my operational costs" and "how can I sell more products?", is a loosing approach to change. While likely to deliver short terms EBITDA gains, it will entrench and crystallize an optimized legacy business process, condemning the enterprise to failure when the next disruption inevitably happens, because there will be no more room to manoeuver.

This is the curse of optimization: we make ourselves slaves to what we are optimizing for. If we optimize for our legacy business process, we are making it very difficult to leave it behind when the disruption comes. If we pick total value creation as our optimization parameter, we create conditions for a continued ability to adapt and thrive in the future.

Comments